- Home

- Anna Humphrey

Mission (Un)Popular Page 3

Mission (Un)Popular Read online

Page 3

Which brings me to the second quality: not very popular. Andrew is my friend, and we hang out with his friends. And, of course, there’s Erika-with-a-K, who I do everything with. So it’s not like I’m so unpopular that nobody talks to me, but Erika and Andrew aren’t exactly Mr. and Mrs. Popularity either. And at my school, you’re either popular or you’re not. It defines who you are, so that’s why I put it on the list.

I think I’ve already explained the talkative/sarcastic part. Like I said, I’m working on it.

“Are we finished?” Mrs. Carlyle looked at us hopefully. I had folded my list into a little accordion and was squeezing it between my fingers for something to do. “I’d like you to swap papers with the person beside you and discuss how you feel about the qualities you’ve listed.”

Em looked as thrilled about the exercise as I did, but I figured I’d a hundred times rather swap with her than with Little Miss Knows-all-the-answers on my left. “Trade?” I asked. She handed me her list.

3 Qualities that describe me, Em Warner:

Rebellious

Spunky

Smart

“Spunky?” I said.

“Yeah,” she said, matter-of-factly.

“That’s…” I was thinking conceited, but I caught myself in time. “Different,” I said, and then, because it hadn’t come out sounding very sincere, I added: “You have really nice handwriting.” She raised her eyebrows and gave me a look like she couldn’t care less.

Then, desperately trying to fill the silence, I said her jeans were cool and asked which she liked better: Lucky jeans, Mavi, or Parasuco. She told me that mostly she just wore vintage. So we talked about where the best stores in the city were. Or at least, I talked and she listened, because it turned out she’d just moved to Darling and she barely knew where the malls were.

Thankfully, Mrs. Carlyle only asked a few groups to present their answers, and she skipped over Em and me, since we were obviously total failures at self-esteem. After that, she made us chant mantras, repeating the words “I am powerful. I am unique,” until our self-worth was affirmed. I glanced at Em out of the corner of my eye. She was sitting with her arms folded, not even pretending to mumble along.

Then we made magazine collages to show our “secret selves.” For some reason, Em cut out all these pictures of fruit, nail polish, and expensive cars. “What?” she said when she saw me looking at it. “I like fruit.” She was obviously trying to mess with Mrs. Carlyle’s mind. My collage had a lot of pictures of girls with perfect creamy skin and straight hair, along with one photo of a tombstone that Em passed me. I don’t even know where she found it. “Put this in,” she whispered. “She’ll think you’re deranged.” Instead, though, the teacher held up my collage and said how powerful it was.

“Symbolically speaking, Margot feels like she’s dying a little on the inside,” she explained. She swept her hand around the circle of peach-skinned models, then tapped the tombstone. “She’s struggling to define her beauty in a society that doesn’t value differences.” Em started laughing softly, and I could barely contain a snort. There was nothing symbolic about it. Other people just took all of the good pictures from the magazines in the pile. By the time I got there, there were mostly ads for skin cream left. And none of them had brown-skinned girls because, let’s face it, magazines almost never do.

Gabriella, the star of self-esteem, had cut out photos of people doing wilderness activities and enjoying family time, and the overweight girl’s entire page was covered with movie stars.

After we finished discussing our collages and did a closing activity, we finally got to go home. Em was the first to leave, getting into the backseat of a black car. She slammed the door. I waved, but through the tinted windows I couldn’t tell if she saw me. A station wagon stopped off next for the red-haired Gabriella, and she climbed into the front seat, talking excitedly to her dad. Overweight Girl and Acne Girl, to my surprise, got into the backseat of the same car, but didn’t say a word to each other. They must have been sisters.

Five minutes later, the van pulled in. My mom had the triplets with her. Aleene was crying hysterically, but I didn’t even turn around to make funny faces to get her to stop.

“Was it a useful class, honey?” my mom yelled over Aleene’s wailing.

“It was pointless!” I yelled back. “Can we just go home?”

She turned to hand a juice box to Aleene, who immediately shut up. “Margot,” she said. “I’m sorry you’re angry with me. I really hoped that class might be helpful. The counselor suggested that low self-esteem could be an issue.”

I stared straight ahead. Obviously, my mom had magically forgotten what it’s like to be almost thirteen. If she remembered, she’d know that sometimes kids my age just screw up (like I admit I did, in a huge way, last June), but even if I did have self-esteem issues, the last thing that was going to make me feel better about myself was a horrible, humiliating class. If she really wanted to make me feel more confident about the new school year, she could give me a fighting chance by taking me to a salon and paying for hair straightening, and maybe getting me some better clothes, or at least doing a tarot reading so I could prepare myself for whatever humiliations I was in for between now and next June.

But speaking of next June…I guess by now you’re probably wondering what happened last June. It’s kind of a painful story to retell, so promise not to laugh too much. Basically, I shoplifted a glazed ham so people would think I was cool. Because I know you’re probably already laughing at me while shaking your head and marveling at what a loser I am, let me tell you why it isn’t actually funny.

It’s not funny because:

It didn’t work. People didn’t start thinking I was cool. Instead, they started to call me “Hamburglar,” which is about as far from a cool nickname as you can get.

I got caught.

My mom and Bald Boring Bryan will probably nevertrust me again.

Did I mention I got caught?

I’ll admit it was a stupid thing to do. What was I planning to do with a glazed ham? If I wanted to steal something, I could have at least gone for something useful, like an iPod.

So why did I do it? Since last June, I’ve been asking myself over and over, and the honest answer is still: I don’t know. I guess I did it because Sarah J. and some of the other popular kids were standing around at lunch near the steps where Erika and I were sitting. One of them dared somebody to sneak out of the yard, go into the grocery store across the street, and steal something. Except that stealing something is no big deal for them. They steal things all the time just to prove that they can: candy bars, gum, lip gloss. Small stuff. That’s why the dare was that the person had to steal something bigger than their head.

I overheard, and without thinking what I was saying (story of my life), I said I’d do it. It was the first time I’d stolen anything, and I swore it would be the last. My mom is always talking about karma: about how the good energy you put out comes back to you, and the same with the bad, and I’m usually thinking about this and holding doors open for ladies with strollers or offering my seat to cranky, funny-smelling old men on the bus.

But last June, in one of those moments where my brain had obviously left my body, I felt this surge of energy go through me, and I just knew I could do it. So I walked into the grocery store and picked up the ham. I didn’t even try to hide it under my shirt or in my bag.

Instead, I held it in my arms, trying to make it look like it was the most normal thing in the world for a twelve-yearold girl to be walking out of the store with a huge chunk of one-hundred-percent grain-fed Canadian meat. I might have actually made it too, if one of the cashiers hadn’t been coming in from her break and if I hadn’t happened to walk right into her. “Sorry,” I mumbled.

“Hey,” she said, “did you pay for that?”

And I’m not sure why—I told her I didn’t.

My mom doesn’t believe in grounding—she says freedom is a basic human right—but she t

old me that if she did, I’d be grounded for life. She also said that she and Bryan were “very disappointed.” I had to agree to see a counselor a few times. Plus, the next day I had to go back to school and face all of the popular kids, who seemed to think it was hilarious that I got arrested.

“You knew we were just kidding, right?” Sarah J. had said, giving me a condescending look. “When we made that bet, nobody was actually going to do it.” Then this guy Ken stuffed three ham sandwiches into my backpack when I wasn’t looking, and about ten different people oinked at me.

And not only did The Group disapprove, the other kids were just as unimpressed. This girl Michelle told me stories about how her cousin couldn’t even get a job at McDonald’s because he’d stolen a stereo when he was eighteen and got a permanent criminal record. Andrew’s friend Amir brought me a lavender-scented note from his mom. She works with troubled youth groups at their mosque and offered to meet with me if I needed guidance. Even Andrew, who’s always nice to me, gave me a worried look and asked why I did it.

Basically, everybody thought I was a moron, myself included. It had been the worst experience of my life. I’d been trying to block it out of my mind all summer, and so far I’d been doing pretty well.

Erika had been helping a lot. We met every weekday at 12:30 so we could make nachos before Charmed and Dazed came on. She shredded the cheese and I took care of the rest. Layering nachos is a fine art and—not to brag—I’m an expert. When we lived alone, my mom and I used to make them every Saturday night.

In the afternoons, if I didn’t have to babysit, we’d either go swimming in Erika’s giant pool, go to the mall and not buy anything, try to make the perfect playlist, practice juggling different kinds of fruit (oranges were easiest, peaches were a disaster), go to the coffee shop, or do whatever else we could think of.

Erika had even been trying to convince me that having been arrested would make me seem dangerous, and that when we got to high school, guys would think that was hot. I wasn’t so sure. Maybe if I’d been caught recklessly driving a really cool motorcycle…But shoplifting meat just didn’t have the same edge to it.

Still. I appreciated her trying to make me feel better. She was the best best friend on earth. I couldn’t imagine my life without her.

3

I Am Devastated Beyond Belief, and Then Some

THEN, THE WORST IMAGINABLE thing happened. I became a miserable, weeping disaster. A sad shadow of my former self. A pathetic, shriveled, liquefied pumpkin that had been rotting on a doorstep since last Halloween. And that doesn’t even begin to describe how devastated I was.

After spending the morning confirming my lack of self-esteem, I had never been more ready to spend an afternoon with my best friend. I couldn’t wait to tell her the entire shameful story, right down to the final activity where Mrs. Carlyle switched off the fluorescents and made us each hold a candle to symbolize shining our light.

And, of course, once that was out of the way, Erika and I already had our whole afternoon planned. After we were done picking my School Year’s Day outfit, we were going to head to Erika’s so she could try on her clothes, which is all Mexx and Lucky Brand stuff that her mom buys when it’s not even on sale. Because all her mom does is shop. (How perfect is her mom?) And when that was over, we were going to take the bus to the mall so we could try on this magical Miss Sixty shirt that looks good on both of us. It’s black and loose with a stretchy bottom, so it hides Erika’s stomach (which isn’t flabby at all, but she says it is) and disguises my twiggishness. Even if I couldn’t afford to buy it, at least I could be in its presence.

But none of that ever happened, because Erika didn’t show up.

For a while I figured her mom was probably just making her vacuum the stairs or something, but when Charmed and Dazed finished, and she was nowhere in sight, I started to worry.

I thought maybe there’d been a mix-up and she’d gone straight to Java House, so I put on my shoes and yelled to Grandma Betty that I was going to the coffee shop. But when I got there, the place was empty, except for the way-older semi-cute coffee guy who Erika had a mini crush on (the other reason we’d been learning to like coffee all summer). So then I walked to her place. But when I got there, her mom said, “Oh, Margot. I don’t know where Erika is. She stormed out. She probably went to your house.”

So I ran back to my house. By this time I was sweaty and sort of mad, but the minute I saw Erika, I forgot about that. She was slumped over, resting her arms on our kitchen table, crying so hard her shoulders were shaking.

My mom was making her a cup of tea with honey, which is her cure for everything. “This is organic alfalfa honey made by free-range bees, Erika,” she was explaining, as if Erika, in the state she was in, should be worried about the welfare of bees—except that, knowing her, she probably was. “Oh, Margot,” Mom said when she saw me, “I’m glad you’re back. I’ll leave you girls to talk.” She put the tea on the table and left, closing the sliding door behind her.

All I could do was look at Erika and wait for her to say something. Anything. She kept trying to catch her breath long enough to get words out between sobs. Finally she managed: “It’s…s-so crappy.”

“What?” I reached out and put my hand on top of hers.

“I’m not g-going to Manning.”

“What do you mean you’re not going to Manning? School starts on Tuesday.”

“I’m going to S-Sacred Heart,” she answered, her voice cracking halfway through.

“The private school?” I said. “The religious one for girls? You can’t! You aren’t even religious.” None of it was making sense. I started to get hysterical. “You HAVE to go to Manning. Sacred Heart? That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard.” I was almost yelling at her.

“My mom is making me go,” Erika sniffed. Her nose was running, so I grabbed a paper towel and shoved it across the table.

“I can’t believe this. Why would she do that?”

Erika got really quiet. Tears were streaming down her cheeks, and she seemed almost afraid of me as she whispered the next part. “She thinks there won’t be as many bad influences at Sacred Heart.”

The words hit me like a soccer ball to the stomach. I knew instantly that it was my fault. Me and my stupid glazed ham.

“It isn’t because of you,” Erika tried to reassure me. “My mom says it’s because of Sarah J. and the other kids who pressured you. She put me on the waiting list in June, and a space opened up today. She just told me. It’s so dumb.”

Now I was about to burst into tears. Of all the bad things that had happened because of (said in a whisper) last June, from the police showing up, to the look of disappointment on my grandma’s face, to the mind-numbingly boring self-esteem workshop that morning…this was the worst punishment I could ever receive. I was going to lose my best friend. And not only was I going to lose her, she was being sentenced to private school, complete with ugly plaid uniforms, religion classes, and no boys, and it was my fault. I was officially the worst best friend on earth.

“Margot, I’m sorry.” I could hardly believe she was trying to comfort me at a time like this. “Margot, don’t cry.”

How was I going to face a single day of seventh grade without Erika? Who was going to help me divide fractions and figure out what was going on in French class? Who was going to sit with me, secretly drawing pictures of Sarah J. as a vampire bat after she suggested I should “really comb my hair before leaving for school”? Or listen to my endless gushing about Gorgeous George? Who was I going to eat lunch with? Walk home with? I would be utterly best-friendless. An outcast. A miserable, hallway-roaming loser. This just wasn’t okay.

“I know!” I said, suddenly coming up with a brilliant plan. “I’ll go to Sacred Heart too. I just have to convince my mom that public school is an evil influence. That shouldn’t be hard.”

Erika blinked. “Really? You’d do that for me?”

“Of course!”

“But you’d h

ave to wear a uniform.”

“Uniforms can be hot.”

“And you’d have to go to church.”

“Notta problem!” I practically sang. “Bring on the church.”

“And there aren’t any guys.”

I admit that last one made me hesitate, but only for a second. “What does it matter?” I sighed. “Gorgeous George is the only guy for me and he barely knows I exist.”

Plus, I thought, it could be a fresh start. None of the Catholic school girls would have seen the yearbook picture of me eating soup. They wouldn’t remember the time when (while trying to answer a question about how insulation conserves heat energy) I accidentally called our science teacher fat. Best of all, I’d lose the nickname Hamburglar. Really, me and Erika going to Sacred Heart was the ideal solution.

Unfortunately, my mom didn’t see it that way.

“Oh Margot. I know you want to be with Erika, but the answer is no,” she said when I cornered her in the kitchen later that day. She was trying to clean crushed blackberries out of Alice’s hair with a Kleenex.

“But Mom,” I reasoned, “can’t you see that public school is corrupting me? I need to be in an environment more conducive to learning and less conducive to criminal behavior.”

She smiled, which I thought was insensitive. “Hold still, please, Alice,” she said, then sighed and gave up. “I guess it’s bath night anyway.” She threw away the Kleenex before opening the freezer and taking out a package of tofu burgers.

“Why? Why won’t you let me go? At least explain.”

“It’s just not practical, Margot. And it’s not who we are.” She tried to separate the frozen burgers with a knife, but they wouldn’t come loose. “First of all, we aren’t Catholic. But more important, public school is giving you opportunities to grow as an individual. It exposes you to people from different backgrounds and socioeconomic classes—unlike private school, where most students come from the upper class. Which brings me to my last point.” She stuck the knife in farther and the burgers finally came apart, flying in opposite directions. One landed on the floor. She picked it up and washed it under the tap. “Do you have any idea how much tuition for private school is?” I didn’t. “It can be upward of fifteen thousand dollars a year,” she said, turning on the frying pan.

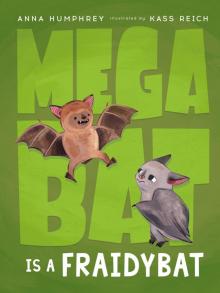

Megabat Is a Fraidybat

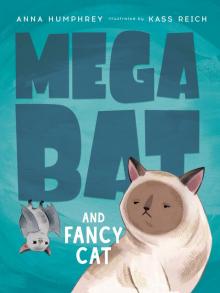

Megabat Is a Fraidybat Megabat and Fancy Cat

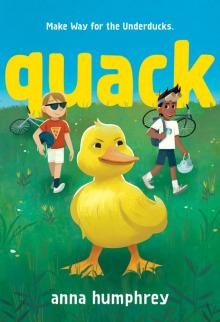

Megabat and Fancy Cat Quack

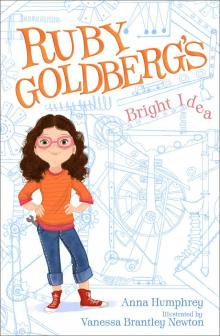

Quack Ruby Goldberg’s Bright Idea

Ruby Goldberg’s Bright Idea Rhymes with Cupid

Rhymes with Cupid Mission (Un)Popular

Mission (Un)Popular Megabat

Megabat